In a recent blog post AT&T claims the best way to encourage broadband deployment in rural America is to establish “stringent build requirements” for winning bidders in the broadcast incentive auction. The funny thing is that AT&T has a long history of promising to build out broadband to consumers – then failing to deliver on those promises – and not just in rural areas, but in urban areas as well.

Take AT&T’s promise in 2006 that if the FCC would just approve its mega-merger with BellSouth, AT&T would make broadband Internet service available to every single household in the market area. Six years later, residents in rural Mississippi were still waiting for high speed Internet. That’s a long time to wait for a webpage to load.

And what about AT&T’s claim in 2011 during its failed takeover attempt of T-Mobile that it desperately needed our wireless spectrum to bring 4G services to 95% of Americans, including rural communities and small towns? Turns out, that statement was not accurate either. Within months after the FCC denied the acquisition, AT&T announced plans to expand its LTE network to cover 94.3% of American consumers—without T-Mobile’s help.

In its latest round of hyperbole, AT&T has brazenly announced that if the FCC approves its purchase of DirecTV, it will bring fiber-to-the-home to two million customers. But as far back as 2012, well before any deal was struck with DirecTV, AT&T said it would expand its fiber network by about 8.5 million additional customer locations by the end of this year.

AT&T’s practice of making promises it cannot keep is matched only by its ability to make claims that cannot withstand scrutiny. In the run-up to the 600 MHz auction, for instance, AT&T has derided the spectrum reserve as a “set aside” that “picks winners and losers.”

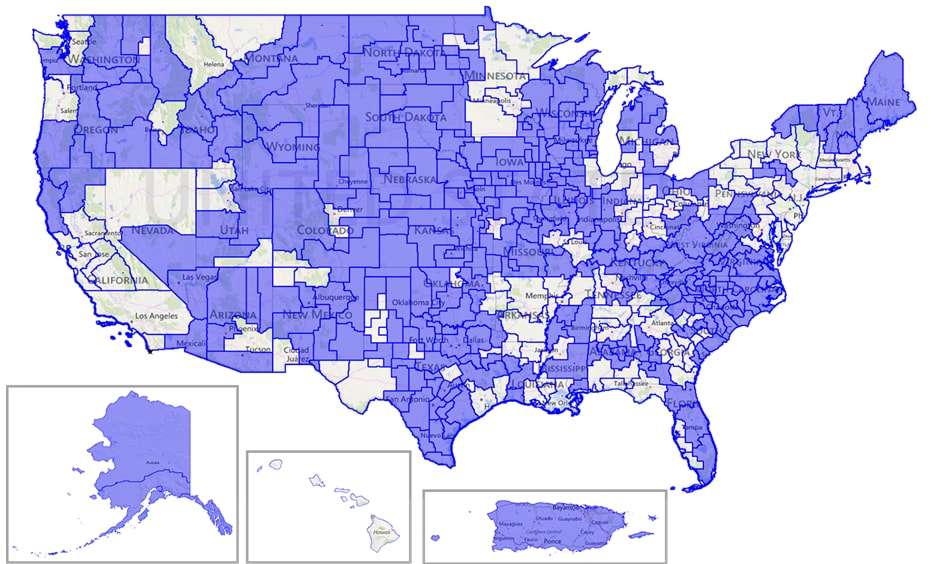

The claim is laughable: if the reserve is a set-aside, it is a set-aside that AT&T or Verizon can claim in nearly three-quarters of the country. The map below shows the markets where AT&T or Verizon can purchase all the spectrum blocks available in the upcoming 600 MHz auction.

The truth is that the spectrum reserve is a contingent, market-based safeguard to prevent the two dominant carriers that already control three-quarters of all low-band spectrum from choking off access to the last remaining amount of this critical input resource.

- The reserve is market specific: where AT&T or Verizon holds less than one-third of all of the low-band resources, AT&T or Verizon can purchase all of the blocks available in that market, as the map above shows.

- The reserve is market based: the reserve does not come into being until after the auction raises enough funds to cover all broadcaster expenses and all other statutory funding goals.

- And the reserve is quite small: the reserve is a maximum of only three of the up to ten blocks that the auction will make available. The reserve is so small, in fact, that it cannot support more than, at most, one meaningful rival to AT&T and Verizon.

The narrow, contingent and limited nature of the three-block reserve helps explain why virtually every wireless operator and entrant except AT&T and Verizon – from small operators such as Bluegrass Cellular and Chat Mobility to mid-sized carriers such as C Spire to potential new entrants such as DISH and Charter Communications – have urged the FCC to do more than it has to protect consumers against the anti-competitive tactics of AT&T and Verizon.

The currently planned three-block reserve is simply not large enough to allow more than one carrier to acquire the two blocks of spectrum that AT&T has referred to as "table stakes" for LTE deployment. Unless the FCC expands the reserve, smaller rivals stand a very substantial chance of failing to secure the spectrum that is critical to providing service inside buildings and across less densely populated areas. The Department of Justice has recognized the possibility that AT&T and Verizon will use their reserve eligibility in rural areas to raise rivals’ costs or foreclose competition. Making the reserve one block larger makes the likely foreclosure strategy that has concerned small and rural carriers – and the DOJ – harder for the two dominant carriers to achieve.

The benefits of increasing the size of the spectrum reserve, and by extension competition in the wireless broadband market, are enormous. AT&T’s and Verizon’s competitive advantages, rooted in their legacy holdings of low-band spectrum largely given to their predecessors for free, mean they generally have not competed on price. Today Verizon and AT&T take in 70% of all revenue in the wireless sector and for good reason: T-Mobile’s average revenue per customer is about $10 less than either AT&T or Verizon. The Big Two’s overwhelming dominance in low-band spectrum holdings, and the coverage advantages that brings, allows them to refuse to budge on prices to consumers and is the biggest barrier to a more competitive wireless market. Little wonder that AT&T and Verizon are so desperate to keep their competitive advantage—so they do not have to lower prices for their combined base of 220 million customers.

If T-Mobile and other competitors can secure fair access to low-band spectrum, AT&T and Verizon will finally face meaningful competition in urban and rural areas. The battle for market share will be fierce, but consumers are the ultimate beneficiaries: if AT&T and Verizon were forced to compete with T-Mobile on price, their customers alone would save roughly $200 billion over the next decade.

That’s why T-Mobile has taken such heroic measures to increase access to low-band spectrum. Expanding the reserve to at least 40 megahertz promises to stimulate innovation, lower consumer prices, increase investment, and accelerate wireless broadband deployment. And unlike AT&T’s repeated empty claims and false statements, these promises are ones we can expect a more competitive wireless market to keep.